By Sarah Jane Lambie – Micro Economy Teacher

This term we welcome Rebecca Faulkner to the Kawakawa team. Rebecca is an experienced high school teacher, now business co-owner of Espresso Rescue, and works on Friday afternoons in the prefab training small groups of our Y9 – 10 rangatahi in the fine art of making coffee.

Each course consists of four, two hour sessions. While on the course, trainee baristas are expected to use their independent work time on Mondays to hone their learnings. Once they have ‘graduated’ as baristas, students have opportunities to work in KCC&C (Kawakawa Coffee Cart & Canteen), at Coffee House pop-up café and at various school events where we know an opportunity to buy a great coffee is welcomed by the parent (and teaching) community!

The barista training is a hands-on course, balanced with some science and a look at the back story – where does coffee come from, how does it get to us, and why does it matter? Rebecca explains that

On average it is going to take around five years for a seed to grow into a plant, and then go on a series of processes to get to our cups. A single tree will produce on average 0.9kg of fruit a year! So, each cup of coffee we make has been a long time in the making – let’s make each coffee we make count!

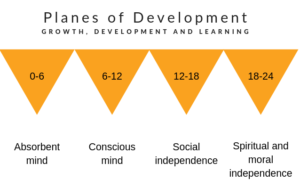

Teaching rangatahi about the interconnectedness between humans and the environment is fundamental to Montessori pedagogy. Through this holistic approach, rangatahi come to understand and take responsibility for their place in the social world as well as the living world.

”This is in contrast to the old idea which was that life in the environment meant to get as much as possible from it; today ideas are very different. Now, it is realized that each animal behaves in a particular way, not only for his own good, but because he works also for the environment. He is an agent who works for the harmonious correlation of all things”

Maria Montessori., Citizen of the World, p19

Working as a Kawakawa barista is one of the many opportunities we offer rangatahi to engage in the real-world activity of making, marketing and selling something they have produced. By experiencing what Dr Montessori called human interdependence (division of labour and exchange of goods and services to meet human needs) our students are learning, at a micro level, how society is organised along with how to develop skills, and utilise their strengths and interests, in collaboration with people and the environment, to meet the challenges they will face in the adult world.

“We must study the correlation between life and its environment. In nature everything correlates. This is the method of nature. Nature is not concerned with the conservation of individual life: it is a harmony, a plan of construction. Everything fits into the plan: winds, rocks, earth, water, plants, man, etc.”

Maria Montessori., Citizen of the World, p22

Looking forward to seeing you at the Kawakawa coffee cart sometime soon!